ALFRED “THE GREAT,” KING of ENGLAND b 848 and Ealhswith Queen of England b 852

Alfred “The Great”19 King of England , born 0849 in Wantage, Berkshire, Dorset, England; died 26 Oct 0901 in Winchester, Hampshire, England; buried 26 Oct 0899 in Hyde Abbey, Winchester, son of 219. Ethelwulf King of Wessex  and 220. Osburga Queen of Wessex . He married in 0868 216. Ealhswith Queen of England , born 0852 in Mercia, England; died 5 Dec 0905; buried 5 Dec 0905 in Winchester Cathedral, England, daughter of 221. Ethelred “Mucil” Duke of Mercia and 222. Eadburh Fadburn .

Alfred “The Great”19 King of England , born 0849 in Wantage, Berkshire, Dorset, England; died 26 Oct 0901 in Winchester, Hampshire, England; buried 26 Oct 0899 in Hyde Abbey, Winchester, son of 219. Ethelwulf King of Wessex  and 220. Osburga Queen of Wessex . He married in 0868 216. Ealhswith Queen of England , born 0852 in Mercia, England; died 5 Dec 0905; buried 5 Dec 0905 in Winchester Cathedral, England, daughter of 221. Ethelred “Mucil” Duke of Mercia and 222. Eadburh Fadburn .

Children of Alfred “The Great” King of England and Ealhswith Queen of England were as follows:

Efridam Princess of England , born 0877 in Wessex, England; died 0929; buried 0929 in St Peter’s Abbey, Ghent, Belgium. She married Baudouin II “The Bald” Count of Flanders , born 0864 in Nord, France; died 10 Sep 0918 in Gent, Flandre Orientale, Belgium, son of Baudouin I Count of Flanders and Adela de Vermandois .

Alfred the Great (Old English: “elf counsel” was King of Wessex from 871 to 899. Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet “the Great”. Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself “King of the Anglo-Saxons”. Details of his life are described in a work by the 10th century Welsh scholar and bishop Asser. Alfred was a learned man who encouraged education and improved his kingdom’s legal system and military structure. He is regarded as a saint by some Catholics, but has never been officially canonized. The Anglican Communion venerates him as a Christian hero, with a feast day of 26 October, and he may often be found depicted instained glass in Church of England parish churches.

Alfred was born in the village of Wanating, nowWantage, Oxfordshire. He was the youngest son of KingÃthelwulf of Wessex, by his first wife,Osburga. In 868 Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of Ãthelred Mucil. At the age of five years, Alfred is said to have been sent to Rome where, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle he was confirmed by Pope Leo IV who “anointed him as king”. Victorian writers interpreted this as an anticipatory coronation in preparation for his ultimate succession to the throne of Wessex. However, his succession could not have been foreseen at the time, as Alfred had three living elder brothers. A letter of Leo IV shows that Alfred was made a “consul“; a misinterpretation of this investiture, deliberate or accidental, could explain later confusion. It may also be based on Alfred’s later having accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Rome where he spent some time at the court of Charles the Bald, King of the Franks, around 854-855. On their return from Rome in 856, Ãthelwulf was deposed by his son Ãthelbald. With civil war looming, the magnates of the realm met in council to hammer out a compromise. Ãthelbald would retain the western shires (i.e., traditional Wessex), and Ãthelwulf would rule in the east. King Ãthelwulf died in 858; meanwhile Wessex was ruled by three of Alfred’s brothers in succession.

Bishop Asser tells the story of how as a child Alfred won a prize of a volume of poetry in English, offered by his mother to the first of her children able to memorize it. This story may be true, or it may be a myth intended to illustrate the young Alfred’s love of learning. Legend also has it that the young Alfred spent time in Ireland seeking healing. Alfred was troubled by health problems throughout his life. It is thought that he may have suffered from Crohn’s disease. Statues of Alfred in Winchester and Wantage portray him as a great warrior. Evidence suggests he was not physically strong, and though not lacking in courage, he was more noted for his intellect than a warlike character.

During the short reigns of the older two of his three elder brothers, Ãthelbald of Wessex andAthelbert of Wessex, Alfred is not mentioned. However, his public life began with the accession of his third brother, Ãthelred of Wessex, in 866. It is during this period that Bishop Asser applied to him the unique title of “secundarius”, which may indicate a position akin to that of the Celtic tanist, a recognised successor closely associated with the reigning monarch. It is possible that this arrangement was sanctioned by Alfred’s father, or by the Witan, to guard against the danger of a disputed succession should Athelred fall in battle. The arrangement of crowning a successor as royal prince and military commander is well known among other Germanic tribes, such as the Swedes and Franks, to whom the Anglo-Saxons were closely related.

In 868, Alfred is recorded as fighting beside Athelred in an unsuccessful attempt to keep the invading Danes out of the adjoining Kingdom of Mercia. For nearly two years, Wessex was spared attacks because Alfred paid the Vikings to leave him alone. However, at the end of 870, the Danes arrived in his homeland. The year which followed has been called “Alfred’s year of battles”. Nine engagements were fought with varying outcomes, though the place and date of two of these battles have not been recorded. In Berkshire, a successful skirmish at theBattle of Englefield on 31 December 870 was followed by a severe defeat at the siege and Battle of Reading on 5 January 871; then, four days later, Alfred won a brilliant victory at the Battle of Ashdown on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. Alfred is particularly credited with the success of this latter battle. However, later that month, on 22 January, the English were defeated at the Battle of Basing and, on the 22 March at the Battle of Merton (perhaps Marden in Wiltshire or Martin in Dorset), in which Ãthelred was killed. The two unidentified battles may have occurred in between.

In 868, Alfred is recorded as fighting beside Athelred in an unsuccessful attempt to keep the invading Danes out of the adjoining Kingdom of Mercia. For nearly two years, Wessex was spared attacks because Alfred paid the Vikings to leave him alone. However, at the end of 870, the Danes arrived in his homeland. The year which followed has been called “Alfred’s year of battles”. Nine engagements were fought with varying outcomes, though the place and date of two of these battles have not been recorded. In Berkshire, a successful skirmish at theBattle of Englefield on 31 December 870 was followed by a severe defeat at the siege and Battle of Reading on 5 January 871; then, four days later, Alfred won a brilliant victory at the Battle of Ashdown on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. Alfred is particularly credited with the success of this latter battle. However, later that month, on 22 January, the English were defeated at the Battle of Basing and, on the 22 March at the Battle of Merton (perhaps Marden in Wiltshire or Martin in Dorset), in which Ãthelred was killed. The two unidentified battles may have occurred in between.

In April 871, King Ãthelred died, and Alfred succeeded to the throne of Wessex and the burden of its defence, despite the fact that Ãthelred left two under-age sons, Ãthelhelm and Ãthelwold. This was in accordance with the agreement that Ãthelred and Alfred had made earlier that year in an assembly at Swinbeorg. The brothers had agreed that whichever of them outlived the other would inherit the personal property that King Ãthelwulf in his will had left jointly to his sons. The deceased’s sons would receive only whatever property and riches their father had settled upon them and whatever additional lands their uncle had acquired. The unstated premise was that the surviving brother would be king. Given the ongoing Danish invasion and the youth of his nephews, Alfred’s succession probably went uncontested. Tensions between Alfred and his nephews, however, would arise later in his reign.

While he was busy with the burial ceremonies for his brother, the Danes defeated the English in his absence at an unnamed spot, and then again in his presence at Wilton in May. The defeat at Wilton smashed any remaining hope that Alfred could drive the invaders from his kingdom. He was forced, instead, to make peace with them. The sources do not tell what the terms of the peace were. Bishop Asser claimed that the ‘pagans’ agreed to vacate the realm and made good their promise; and, indeed, the Viking army did withdraw from Reading in the autumn of 871 to take up winter quarters in Mercian London. Although not mentioned by Asser or by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Alfred probably also paid the Vikings cash to leave, much as the Mercians were to do in the following year. Hoards dating to the Viking occupation of London in 871/2 have been excavated at Croydon, Gravesend, and Waterloo Bridge; these finds hint at the cost involved in making peace with the Vikings. For the next five years, the Danes occupied other parts of England. However, in 876 under their new leader,Guthrum, the Danes slipped past the English army and attacked and occupied Wareham in Dorset. Alfred blockaded them but was unable to take Wareham by assault. Accordingly, he negotiated a peace which involved an exchange of hostages and oaths, which the Danes swore on a “holy ring” associated with the worship of Thor. The Danes, however, broke their word and, after killing all the hostages, slipped away under cover of night to Exeter in Devon. There, Alfred blockaded them, and with a relief fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to submit. They withdrew to Mercia, but, in January 878, made a sudden attack on Chippenham, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas, “and most of the people they killed, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney in the marshes of Somerset, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe”. From his fort at Athelney, an island in the marshes near North Petherton, Alfred was able to mount an effective resistance movement, rallying the local from Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire.

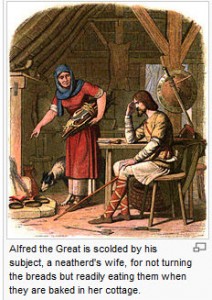

A popular legend, originating from 12th century chronicles, tells how when he first fled to the Somerset Levels, Alfred was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn.

A popular legend, originating from 12th century chronicles, tells how when he first fled to the Somerset Levels, Alfred was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn.

870 was the low-water mark in the history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. With all the other kingdoms having fallen to the Vikings, Wessex alone was still resisting. In the seventh week after Easter [ May 878], around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to Egbert’s Stone east of Selwood, where he was met by “all the people of Somerset and of Wiltshire and of that part of Hampshire which is on this side of the sea [that is, west of Southampton Water], and they rejoiced to see him” Alfreds emergence from his marshland stronghold was part of a carefully planned offensive that entailed raising the fyrds of three shires. This meant not only that the king had retained the loyalty of ealdormen, royal reeves and kings thegns (who were charged with levying and leading these forces), but that they had maintained their positions of authority in these localities well enough to answer Alfreds summons to war. Alfreds actions also suggest a finely honed system of scouts and messengers. Alfred won a decisive victory in the ensuing Battle of Ethandun, which may have been fought near Westbury, Wiltshire. He then pursued the Danes to their stronghold at Chippenham and starved them into submission. One of the terms of the surrender was that Guthrum convert to Christianity; and three weeks later the Danish king and 29 of his chief men were baptised at Alfred’s court at Aller, near Athelney, with Alfred receiving Guthrum as his spiritual son. The “unbinding of the chrism” took place with great ceremony eight days later at the royal estate at Wedmore in Somerset, after which Guthrum fulfilled his promise to leave Wessex. There is no contemporary evidence that Alfred and Guthrum agreed upon a formal treaty at this time; the so-called Treaty of Wedmore is an invention of modern historians. The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, preserved in Old English in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (Manuscript 383), and in a Latin compilation known as Quadripartitus, was negotiated later, perhaps in 879 or 880, when King Ceolwulf II of Mercia was deposed. That treaty divided up the kingdom of Mercia. By its terms the boundary between Alfreds and Guthrums kingdoms was to run up the River Thames, to the River Lea; follow the Lea to its source (near Luton); from there extend in a straight line to Bedford; and from Bedford follow the River Ouse toWatling Street. In other words, Alfred succeeded to Ceolwulfs kingdom, consisting of western Mercia; and Guthrum incorporated the eastern part of Mercia into an enlarged kingdom of East Anglia (henceforward known as the Danelaw). By terms of the treaty, moreover, Alfred was to have control over the Mercian city of London and its mints at least for the time being. The disposition of Essex, held by West Saxon kings since the days of Egbert, is unclear from the treaty, though, given Alfreds political and military superiority, it would have been surprising if he had conceded any disputed territory to his new godson.

With the signing of the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, an event most commonly held to have taken place around 880 when Guthrums people began settling East Anglia, Guthrum was neutralized as a threat. In conjunction with this agreement an army of Danish left the island and sailed to Ghent. Alfred however was still forced to contend with a number of Danish threats. A year later in 881 Alfred fought a small sea battle against four Danish ships On the high seas. Two of the ships were destroyed and the others surrendered to Alfreds forces. Similar small skirmishes with independent Viking raiders would have occurred for much of the period as they had for decades.

In the year 883, though there is some debate over the year, King Alfred because of his support and his donation of alms to Rome received a number of gifts from the Pope Marinus. Among these gifts was reputed to be a piece of the true cross, a true treasure for the devout Saxon king. According to Asser because of Pope Marinus friendship with King Alfred the pope granted an exemption to any Anglo-Saxons residing within Rome from tax or tribute.

After the signing of the treaty with Guthrum, Alfred was spared any large scale conflicts for some time. Despite this relative peace the king was still forced to deal with a number of Danish raids and incursions. Among these was a raid taking place in Kent, an allied country in Southeast England during the year 885, quite possibly the largest raid since the battles with Guthrum. Assers account of the raid places the Danish raiders at the Saxon city of Rochester where they built a temporary fortress in order to besiege the city. In response to incursion Alfred led an Anglo-Saxon force against the Danes who, instead of engaging the army of Wessex, fled to their beached ships and sailed to another part of Britain. The retreating Danish force supposedly left Britain the following summer.

Not long after the failed Danish raid in Kent Alfred dispatched his fleet to East Anglia. The purpose of this expedition is debated, though Asser claims that it was for the sake of plunder. After travelling up the River Stour, the fleet was met by Danish vessels that numbered 13 or 16 (sources vary on the number) and a battle ensued. The Anglo-Saxon Fleet emerged victorious and as Huntingdon accounts laden with spoils. The victorious fleet was then caught unaware when attempting to leave the River Stour and was attacked by a Danish force at the mouth of the river. The Danish fleet was able to defeat Alfred’s fleet which may have been weakened in the previous engagement.

A year later in 886 Alfred reoccupied the city of London and set out to make it habitable again. Alfred entrusted the city to the care of his son-in law Ãthelred, ealdorman of Mercia. The restoration of London progressed through the later half of the 880s and is believed to have revolved around a new street plan, added fortifications in addition to the existing Roman walls, and some believe the construction of matching fortifications on the South bank of the River Thames. This is also the time period almost all chroniclers agree the Saxon people of pre-unification England submitted to Alfred. This was not, however, the point in which Alfred came to be known as King of England; in fact he would never adopt the title for himself. In truth the power which Alfred wielded over the English peoples at this time seemed to stem largely from the military might of the West Saxons, Alfreds political connections having the ruler of Mercia as his son-in-law, and Alfreds keen administration talents.

Between the restoration of London and the resumption of large scale Danish attacks in the early 890s Alfreds reign was rather uneventful. The relative peace of the late 880s was marred by the death of Alfred’s sister, Ãthelswith, who died en route to Rome in 888. In the same year the Archbishop of Canterbury, Ãthelred also passed away. One year later Guthrum, or Athelstan by his baptized name, Alfreds former enemy and king of East Anglia died and was buried in Hadleigh, Suffolk. Guthrums passing marked a change in the political sphere Alfred dealt with. Guthrums death created a power vacuum which would stir up other power hungry warlords eager to take his place in the following years. The quiet years of Alfreds life were coming to a close, and war was on the horizon.

After another lull, in the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again. Finding their position in mainland Europe precarious, they crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body at Appledore, Kent, and the lesser, under Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from which he could observe both forces. While he was in talks with Hastein, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck northwestwards. They were overtaken by Alfred’s oldest son, Edward, and were defeated in a general engagement at Farnham in Surrey. They took refuge on an island in the Hertfordshire Colne, where they were blockaded and were ultimately forced to submit. The force fell back on Essex and, after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, coalesced with Hastein’s force at Shoebury.

Alfred had been on his way to relieve his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter and an unnamed stronghold on the North Devon shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and raised the Siege of Exeter. The fate of the other place is not recorded. Meanwhile, the force under Hastein set out to march up the Thames Valley, possibly with the idea of assisting their friends in the west. But they were met by a large force under the three great ealdormen of Mercia, Wiltshire andSomerset, and forced to head off to the northwest, being finally overtaken and blockaded at Buttington. Some identify this with Buttington Tump at the mouth of the River Wye, others with Buttington near Welshpool. An attempt to break through the English lines was defeated. Those who escaped retreated to Shoebury. Then, after collecting reinforcements, they made a sudden dash across England and occupied the ruined Roman walls of Chester. The English did not attempt a winter blockade, but contented themselves with destroying all the supplies in the neighbourhood. Early in 894 (or 895), want of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex. At the end of this year and early in 895 (or 896), the Danes drew their ships up the River Thames and River Lea and fortified themselves twenty miles (32 km) north of London. A direct attack on the Danish lines failed but, later in the year, Alfred saw a means of obstructing the river so as to prevent the egress of the Danish ships. The Danes realised that they were outmanoeuvred. They struck off north-westwards and wintered at Cwatbridge near Bridgnorth. The next year, 896 (or 897), they gave up the struggle. Some retired to Northumbria, some to East Anglia. Those who had no connections in England withdrew back to the continent

The near-disaster of the winter of 878, even more than the victory in the spring, left its mark on the king and shaped his subsequent policies. Â Over the last two decades of his reign, Alfred undertook a radical reorganisation of the military institutions of his kingdom, strengthened the West Saxon economy through a policy of monetary reform and urban planning and strove to win divine favour by resurrecting the literary glories of earlier generations of Anglo-Saxons. Alfred pursued these ambitious programmes to fulfil, as he saw it, his responsibility as king. This justified the heavy demands he made upon his subjects’ labour and finances. It even excused the expropriation of strategically located Church lands. Recreating the fyrd into a standing army, ringing Wessex with some thirty garrisoned fortified towns, and constructing new and larger ships for the royal fleet were costly endeavours that provoked resistance from noble and peasant alike. But they paid off. When the Vikings returned in force in 892 they found a kingdom defended by a standing, mobile field army and a network of garrisoned fortresses that commanded its navigable rivers and Roman roads.

Alfred analysed the defects of the military system that he had inherited and implemented changes to remedy them. Alfred’s military reorganisation of Wessex consisted of three elements: the building of thirty fortified and garrisoned towns (burhs) along the rivers and Roman roads of Wessex; the creation of a mobile (horsed) field force, consisting of his nobles and their warrior retainers, which was divided into two contingents, one of which was always in the field; and the enhancement of Wessex’s seapower through the addition of larger ships to the existing royal fleet. Each element of the system was meant to remedy defects in the West Saxon military establishment exposed by the Viking invasions. If under the existing system he could not assemble forces quickly enough to intercept mobile Viking raiders, the obvious answer was to have a standing field force. If this entailed transforming the West Saxon fyrd from a sporadic levy of king’s men and their retinues into a mounted standing army, so be it. If his kingdom lacked strongpoints to impede the progress of an enemy army, he would build them. If the enemy struck from the sea, he would counter them with his own naval power. Characteristically, all of Alfred’s innovations were firmly rooted in traditional West Saxon practice, drawing as they did upon the three so-called common burdens’ of bridge work, fortress repair and service on the king’s campaigns that all holders of bookland and royal loanland owed the Crown. Where Alfred revealed his genius was in designing the field force and burhs to be parts of a coherent military system. Neither Alfred’s reformed fyrd nor his burhs alone would have afforded a sufficient defence against the Vikings; together, however, they robbed the Vikings of their major strategic advantages: surprise and mobility.

Alfred, in effect, had created what modern strategists call a defence-in-depth system, and one that worked. Alfred’s burhs, or boroughs, were not grand affairs like the massive stone late Roman shore forts that still dot the southern coast of England (e.g. Pevensey and Richborough ‘Castle’). Rather, the borough defences consisted mainly of massive earthworks, large earthen walls surrounded by wide ditches. The earthen walls probably were surmounted with wooden palisades, which by the tenth century were giving way to stone walls. (The Alfredian defences are well preserved at Wareham, a town on the southern coast of England.) The size of the boroughs varied greatly, from tiny fortifications such as Pilton to large towns like Winchester. Many of the boroughs were, in fact, twin towns built on either side of a river and connected by a fortified bridge much like Charles the Bald‘s fortifications a generation before. Such a double-borough would block passage on the river; the Vikings would have to row under a garrisoned bridge, risking being pelted with stones, spears, or shot with arrows, in order to go upstream. Alfred’s thirty boroughs were distributed widely throughout the West Saxon kingdom and situated in such a manner that no part of the kingdom was more than twenty miles, a day’s march, from a fortified centre. They were also sited near fortified royal villas, to permit the king better control over his strongholds. What has not been recognised sufficiently is how these boroughs dominated the kingdom’s lines of communication, the navigable rivers, Roman roads, and major trackways. Alfred seems to have had “highways” (hereweges – “army roads”) linking the boroughs to one another. An extensive beacon system to warn of approaching Viking fleets and armies was probably also instituted at this time. In short, the thirty boroughs formed an integrated system of fortifications. The presence of well-garrisoned boroughs along the major travel routes of Wessex presented an obstacle for Viking invaders, especially those laden with booty. They also served as places of refuge for the populations of the surrounding countryside. But these fortresses were not mere static points of defence. They were designed to operate in conjunction with Alfred’s mobile standing army. The army and the boroughs together deprived the Vikings of their major strategic advantages: surprise and mobility. It was dangerous for the Vikings to leave a borough intact astride their lines of communication, but it was equally dangerous to attempt to take one. Lacking siege equipment or a developed doctrine of siegecraft, the Vikings could not take these fortresses by storm. Rather, they reduced to the expedient of starving them into submission, which gave the king time to come to their relief with his mobile field army, or for the garrisons of neighbouring boroughs to come to the aid of the besieged town. In a number of instances, the hunter became the hunted, as borough garrison and field force joined together to pursue the would-be raiders. In fact, the only recorded success Viking forces had against boroughs in the ninth century occurred in 892, when a Viking stormed a half-made, poorly garrisoned fortress up the Lympne estuary in Kent.

Alfred’s burghal system was revolutionary in its strategic conception and potentially expensive in its execution. As Alfreds biographer Asser makes clear, many nobles were reluctant to comply with what must have seemed to them outrageous and unheard of demands even if they were for the common needs of the kingdom, as Asser reminded them. The cost of building the burhs was great in itself, but this paled before the cost of upkeep for these fortresses and the maintenance of their standing garrisons. A remarkable early tenth-century document, known as the Burghal Hidage, provides a formula for determining how many men were needed to garrison a borough, based on one man for every 5.5 yards (5 meters) of wall. This provided a theoretical total of 27,071 soldiers, which is unlikely to have ever been achieved in practice. Even if we assume that the mobile forces of Alfred were small, perhaps 3,000 or so horsemen, the manpower costs of his military establishment were considerable.

To obtain the needed garrison troops and workers to build and maintain the burhs’ defences, Alfred regularised and vastly expanded the existing (and, one might add, quite recent) obligation of landowners to provide fortress work on the basis of the hidage assessed upon their lands. The allotments of the Burghal Hidage represent the creation of administrative districts for the support of the burhs. The landowners attached to Wallingford, for example, were responsible for producing and feeding 2,400 men, the number sufficient for maintaining 9,900 feet (3 km) of wall. Each of the larger burhs became the centre of a territorial district of considerable size, carved out of the neighbouring countryside in order to support the town. In one sense, Alfred conceived nothing truly new here. The shires of Wessex went back at least to the reign of King Ine, who probably also imposed a hidage assessment upon each for food rents and other services owed the Crown. But, it is equally clear that Alfred did not allow the past to bind him. With the advice of his witan, he freely reorganised and modified what he had inherited. The result was nothing short of an administrative revolution, a reorganisation of the West Saxon shire system to accommodate Alfreds military needs. Even if one rejects the thesis crediting the “Burghal Hidage” to Alfred, what is undeniable is that, in the parts of Mercia acquired by Alfred from the Vikings, the shire system seems now to have been introduced for the first time. This is probably what prompted the legend that Alfred was the inventor of shires, hundreds and tithings.

Alfred also tried his hand at naval design. In 896, he ordered the construction of a small fleet, perhaps a dozen or so longships, that, at 60 oars, were twice the size of Viking warships. This was not, as the Victorians asserted, the birth of the English Navy. Wessex possessed a royal fleet before this. King Athelstan of Kent and Ealdorman Ealhhere had defeated a Viking fleet in 851, capturing nine ships, and Alfred himself had conducted naval actions in 882. But, clearly, the author of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and probably Alfred himself regarded 897 as marking an important development in the naval power of Wessex. The chronicler flattered his royal patron by boasting that Alfred’s ships were not only larger, but swifter, steadier and rode higher in the water than either Danish or Frisian ships. (It is probable that, under the classical tutelage of Asser, Alfred utilised the design of Greek and Roman warships, with high sides, designed for fighting rather than for navigation.) Alfred had seapower in mind: if he could intercept raiding fleets before they landed, he could spare his kingdom from ravaging. Alfred’s ships may have been superior in conception, however in practice they proved to be too large to manoeuvre well in the close waters of estuaries and rivers, the only places in which a ‘naval’ battle could occur. (The warships of the time were not designed to be ship killers but troop carriers. A naval battle entailed a ship’s coming alongside an enemy vessel, at which point the crew would lash the two ships together and board the enemy. The result was effectively a land battle involving hand-to-hand fighting on board the two lashed vessels.)

In the one recorded naval engagement in the year 896, Alfred’s new fleet of nine ships intercepted six Viking ships in the mouth of an unidentified river along the south of England. The Danes had beached half their ships, and gone inland, either to rest their rowers or to forage for food. Alfred’s ships immediately moved to block their escape to the sea. The three Viking ships afloat attempted to break through the English lines. Only one made it, Alfred’s ships intercepted the other two. Lashing the Viking boats to their own, the English crew boarded the enemy’s vessels and proceeded to kill everyone on board. The one ship that escaped managed to do so only because all of Alfred’s heavy ships became mired when the tide went out. What ensued was a land battle between the crews of the grounded ships. The Danes, heavily outnumbered, would have been wiped out if the tide had not risen. When that occurred, the Danes rushed back to their boats, which being lighter, with shallower drafts, were freed before Alfred’s ships. Helplessly, the English watched as the Vikings rowed past them. But the pirates had suffered so many casualties (120 Danes dead against 62 Frisians and English), that they had difficulties putting out to sea. All were too damaged to row around Sussex and two were driven against the Sussex coast. The shipwrecked sailors were brought before Alfred at Winchester and hanged.

In the late 880s or early 890s, Alfred issued a long domboc or law code, consisting of his “own” laws followed by a code issued by his late seventh-century predecessor King Ine of Wessex. Together these laws are arranged into 120 chapters. In his introduction, Alfred explains that he gathered together the laws he found in many ‘synod-books’ and “ordered to be written many of the ones that our forefathers observed–those that pleased me; and many of the ones that did not please me, I rejected with the advice of my councillors, and commanded them to be observed in a different way.” Alfred singled out in particular the laws that he “found in the days of Ine, my kinsman, or Offa, king of the Mercians, or King Ãthelbert of Kent, who first among the English people received baptism.” It is difficult to know exactly what Alfred meant by this. He appended rather than integrated the laws of Ine into his code, and although he included, as had Ãthelbert, a scale of payments in compensation for injuries to various body parts, the two injury tariffs are not aligned. And, Offa is not known to have issued a law code, leading historian Patrick Wormald to speculate that Alfred had in mind the legatine capitulary of 786 that was presented to Offa by two papal legates.

About a fifth of the law code is taken up by Alfred’s introduction, which includes translations into English of the Decalogue, a few chapters from the Book of Exodus, and the so-called ‘Apostolic Letter’ from Acts of the Apostles (15:23-29). The Introduction may best be understood as Alfred’s meditation upon the meaning of Christian law. It traces the continuity between God’s gift of Law to Moses to Alfred’s own issuance of law to the West Saxon people. By doing so, it links the holy past to the historical present and represents Alfred’s law-giving as a type of divine legislation. This is the reason that Alfred divided his code into precisely 120 chapters: 120 was the age at which Moses died and, in the number-symbolism of early medieval biblical exegetes, 120 stood for law. The link between the Mosaic Law and Alfred’s code is the ‘Apostolic Letter,’ which explained that Christ “had come not to shatter or annul the commandments but to fulfill them; and he taught mercy and meekness” (Intro, 49.1). The mercy that Christ infused into Mosaic Law underlies the injury tariffs that figure so prominently in barbarian law codes, since Christian synods “established, through that mercy which Christ taught, that for almost every misdeed at the first offence secular lords might with their permission receive without sin the monetary compensation, which they then fixed.” The only crime that could not be compensated with a payment of money is treachery to a lord, “since Almighty God adjudged none for those who despised Him, nor did Christ, the Son of God, adjudge any for the one who betrayed Him to death; and He commanded everyone to love his lord as Himself.” Alfred’s transformation of Christ’s commandment from “Love your neighbour as yourself” (Matt. 22:39-40) to love your secular lord as you would love the Lord Christ himself underscores the importance that Alfred placed upon lordship, which he understood as a sacred bond instituted by God for the governance of man.

When one turns from the domboc’s introduction to the laws themselves, it is difficult to uncover any logical arrangement. The impression one receives is of a hodgepodge of miscellaneous laws. The law code, as it has been preserved, is singularly unsuitable for use in lawsuits. In fact, several of Alfred’s laws contradict the laws of Ine that form an integral part of the code. Patrick Wormald’s explanation is that Alfred’s law code should be understood not as a legal manual, but as an ideological manifesto of kingship, “designed more for symbolic impact than for practical direction.” In practical terms, the most important law in the code may well be the very first: “We enjoin, what is most necessary, that each man keep carefully his oath and his pledge,” which expresses a fundamental tenet of Anglo-Saxon law.

Alfred devoted considerable attention and thought to judicial matters. Asser underscores his concern for judicial fairness. Alfred, according to Asser, insisted upon reviewing contested judgments made by his ealdormen and reeves, and “would carefully look into nearly all the judgements which were passed [issued] in his absence anywhere in the realm, to see whether they were just or unjust.” A charter from the reign of his son Edward the Elder depicts Alfred as hearing one such appeal in his chamber, while washing his hands. Asser represents Alfred as a Solomonic judge, painstaking in his own judicial investigations and critical of royal officials who rendered unjust or unwise judgments. Although Asser never mentions Alfred’s law code, he does say that Alfred insisted that his judges be literate, so that they could apply themselves “to the pursuit of wisdom.” The failure to comply with this royal order was to be punished by loss of office. It is uncertain how seriously this should be taken; Asser was more concerned to represent Alfred as a wise ruler than to report actual royal policy.

Asser speaks grandiosely of Alfred’s relations with foreign powers, but little definite information is available. His interest in foreign countries is shown by the insertions which he made in his translation of Orosius. He certainly corresponded with Elias III, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, and possibly sent a mission to India in honour of Saint Thomas the Apostle, whose tomb was believed to lie in that country. Contact was also made with the Caliph in Baghdad. Embassies to Rome conveying the English alms to the Pope were fairly frequent. Around 890, Wulfstan of Haithabu undertook a journey from Haithabu on Jutland along the Baltic Sea to the Prussiantrading town of Truso. Alfred ensured he reported to him details of his trip.

Alfred’s relations with the Celtic princes in the western half of Britain are clearer. Comparatively early in his reign, according to Asser, the southern Welsh princes, owing to the pressure on them from North Wales and Mercia, commended themselves to Alfred. Later in the reign the North Welsh followed their example, and the latter cooperated with the English in the campaign of 893 (or 894). That Alfred sent alms to Irish and Continental monasteries may be taken on Asser’s authority. The visit of the three pilgrim “Scots” (i.e. Irish) to Alfred in 891 is undoubtedly authentic. The story that he himself in his childhood was sent to Ireland to be healed by Saint Modwenna, though mythical, may show Alfred’s interest in that island.

In the 880s, at the same time that he was “cajoling and threatening” his nobles to build and man the burhs, Alfred, perhaps inspired by the example of Charlemagne almost a century before, undertook an equally ambitious effort to revive learning. It entailed the recruitment of clerical scholars from Mercia, Wales and abroad to enhance the tenor of the court and of the episcopacy; the establishment of a court school to educate his own children, the sons of his nobles, and intellectually promising boys of lesser birth; an attempt to require literacy in those who held offices of authority; a series of translations into the vernacular of Latin works the king deemed “most necessary for all men to know” the compilation of a chronicle detailing the rise of Alfred’s kingdom and house; and the issuance of a law code that presented the West Saxons as a new people of Israel and their king as a just and divinely inspired law-giver.

Very little is known of the church under Alfred. The Danish attacks had been particularly damaging to the monasteries, and though Alfred founded monasteries at Athelney and Shaftesbury, the first new monastic houses in Wessex since the beginning of the eighth century, and enticed foreign monks to England, monasticism did not revive significantly during his reign. Alfred undertook no systematic reform of ecclesiastical institutions or religious practices in Wessex. For him the key to the kingdom’s spiritual revival was to appoint pious, learned, and trustworthy bishops and abbots. As king he saw himself as responsible for both the temporal and spiritual welfare of his subjects. Secular and spiritual authority were not distinct categories for Alfred. He was equally comfortable distributing his translation of Gregory the Great‘s Pastoral Care to his bishops so that they might better train and supervise priests, and using those same bishops as royal officials and judges. Nor did his piety prevent him from expropriating strategically sited church lands, especially estates along the border with the Danelaw, and transferring them to royal thegns and officials who could better defend them against Viking attacks.

The Danish raids had also a devastating impact on learning in England. Alfred lamented in the preface to his translation of Gregory’sPastoral Care that “learning had declined so thoroughly in England that there were very few men on this side of the Humber who could understand their divine services in English, or even translate a single letter from Latin into English: and I suppose that there were not many beyond the Humber either”. Alfred undoubtedly exaggerated for dramatic effect the abysmal state of learning in England during his youth. That Latin learning had not been obliterated is evidenced by the presence in his court of learned Mercian and West Saxon clerics such as Plegmund, Wferth, and Wulfsige, but Alfred’s account should not be entirely discounted. Manuscript production in England dropped off precipitously around the 860s when the Viking invasions began in earnest, not to be revived until the end of the century. Numerous Anglo-Saxon manuscripts burnt up along with the churches that housed them. And a solemn diploma from Christ Church, Canterbury dated 873 is so poorly constructed and written that historian Nicholas Brooks posited a scribe who was either so blind he could not read what he wrote or who knew little or no Latin. “It is clear,” Brooks concludes, “that the metropolitan church of Canterbury must have been quite unable to provide any effective training in the scriptures or in Christian worship.”

Following the example of Charlemagne, Alfred established a court school for the education of his own children, those of the nobility, and “a good many of lesser birth.” There they studied books in both English and Latin and “devoted themselves to writing, to such an extent …. they were seen to be devoted and intelligent students of the liberal arts.” He recruited scholars from the Continent and from Britain to aid in the revival of Christian learning in Wessex and to provide the king personal instruction. Grimbald and John the Saxon came from Francia; Plegmund (whom Alfred appointed archbishop of Canterbury in 890), Bishop Werferth of Worcester, Ãthelstan, and the royal chaplains Werwulf, from Mercia; and Asser, from St. David’s in south-western Wales.

Alfred’s educational ambitions seem to have extended beyond the establishment of a court school. Believing that without Christian wisdom there can be neither prosperity nor success in war, Alfred aimed “to set to learning (as long as they are not useful for some other employment) all the free-born young men now in England who have the means to apply themselves to it.” Conscious of the decay of Latin literacy in his realm, Alfred proposed that primary education be taught in English, with those wishing to advance to holy orders to continue their studies in Latin. The problem, however, was that there were few “books of wisdom” written in English. Alfred sought to remedy this through an ambitious court-centred programme of translating into English the books he deemed “most necessary for all men to know.” It is unknown when Alfred launched this programme, but it may have been during the 880s when Wessex was enjoying a respite from Viking attacks.

Apart from the lost Handboc or Encheiridion, which seems to have been a commonplace book kept by the king, the earliest work to be translated was the Dialogues of Gregory the Great, a book greatly popular in the Middle Ages. The translation was undertaken at Alfred’s command by Werferth, Bishop of Worcester, with the king merely furnishing a preface. Remarkably, Alfred, undoubtedly with the advice and aid of his court scholars, translated four works himself: Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, Boethius‘s Consolation of Philosophy, St. Augustine‘s Soliloquies, and the first fifty psalms of the Psalter. One might add to this list Alfred’s translation, in his law code, of excerpts from the Vulgate Book of Exodus. The Old English versions of Orosius‘s Histories against the Pagans and Bede‘sEcclesiastical History of the English People are no longer accepted by scholars as Alfred’s own translations because of lexical and stylistic differences. Nonetheless, the consensus remains that they were part of the Alfredian programme of translation. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge suggest this also for Bald’s Leechbook and the anonymous Old English Martyrology.

Alfred’s first translation was of Pope Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, which he prefaced with an introduction explaining why he thought it necessary to translate works such as this one from Latin into English. Although he described his method as translating “sometimes word for word, sometimes sense for sense,” Alfred’s translation actually keeps very close to his original, although through his choice of language he blurred throughout the distinction between spiritual and secular authority. Alfred meant his translation to be used and circulated it to all his bishops.

Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy was the most popular philosophical handbook of the Middle Ages. Unlike his translation of the Pastoral Care, Alfred here deals very freely with his original and though the late Dr. G. Scheps showed that many of the additions to the text are to be traced not to Alfred himself, but to the glosses and commentaries which he used, still there is much in the work which is solely Alfred’s and highly characteristic of his style. It is in the Boethius that the oft-quoted sentence occurs: “My will was to live worthily as long as I lived, and after my life to leave to them that should come after, my memory in good works.” The book has come down to us in two manuscripts only. In one of thesethe writing is prose, in the other a combination of prose and alliterating verse. The latter manuscript was severely damaged in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the authorship of the verse has been much disputed; but likely it also is by Alfred. In fact, he writes in the prelude that he first created a prose work and then used it as the basis for his poem Metres of Boethius, his crowning literary achievement. He spent a great deal of time working on these books, which he tells us he gradually wrote through the many stressful times of his reign to refresh his mind. Of the authenticity of the work as a whole there has never been any doubt.

The last of Alfred’s works is one to which he gave the name Blostman, i.e., “Blooms” or Anthology. The first half is based mainly on the Soliloquies of St Augustine of Hippo, the remainder is drawn from various sources, and contains much that is Alfred’s own and highly characteristic of him. The last words of it may be quoted; they form a fitting epitaph for the noblest of English kings. “Therefore he seems to me a very foolish man, and truly wretched, who will not increase his understanding while he is in the world, and ever wish and long to reach that endless life where all shall be made clear.

Alfred appears as a character in the twelfth- or thirteenth-century poem The Owl and the Nightingale, where his wisdom and skill with proverbs is praised. The Proverbs of Alfred, a thirteenth-century work, contains sayings that are not likely to have originated with Alfred but attest to his posthumous medieval reputation for wisdom.

The Alfred jewel, discovered in Somerset in 1693, has long been associated with King Alfred because of its Old English inscription “AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN” (Alfred ordered me to be made). The jewel is about 2½ inches (6.1 cm) long, made of filigreed gold, enclosing a highly polished piece of quartz crystal beneath which is set a cloisonn enamel plaque, with an enamelled image of a man holding floriate sceptres, perhaps personifying Sight or the Wisdom of God. It was at one time attached to a thin rod or stick based on the hollow socket at its base. The jewel certainly dates from Alfred’s reign. Although its function is unknown, it has been often suggested that the jewel was one of the pointers for reading that Alfred ordered sent to every bishopric accompanying a copy of his translation of the Pastoral Care. Each was worth the princely sum of 50 mancuses, which fits in well with the quality workmanship and expensive materials of the Alfred jewel.

Historian Richard Abels sees Alfred’s educational and military reforms as complementary. Restoring religion and learning in Wessex, Abels contends, was to Alfred’s mind as essential to the defence of his realm as the building of the burhs. As Alfred observed in the preface to his English translation of Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, kings who fail to obey their divine duty to promote learning can expect earthly punishments to befall their people. The pursuit of wisdom, he assured his readers of the Boethius, was the surest path to power: “Study Wisdom, then, and, when you have learned it, condemn it not, for I tell you that by its means you may without fail attain to power, yea, even though not desiring it”. The portrayal of the West-Saxon resistance to the Vikings by Asser and the chronicler as a Christian holy war was more than mere rhetoric or ‘propaganda’. It reflected Alfred’s own belief in a doctrine of divine rewards and punishments rooted in a vision of a hierarchical Christian world order in which God is the Lord to whom kings owe obedience and through whom they derive their authority over their followers. The need to persuade his nobles to undertake work for the ‘common good’ led Alfred and his court scholars to strengthen and deepen the conception of Christian kingship that he had inherited by building upon the legacy of earlier kings such as Offa as well as clerical writers such as Bede, Alcuin and the other luminaries of the Carolingian renaissance. This was not a cynical use of religion to manipulate his subjects into obedience, but an intrinsic element in Alfred’s worldview. He believed, as did other kings in ninth-century England and Francia, that God had entrusted him with the spiritual as well as physical welfare of his people. If the Christian faith fell into ruin in his kingdom, if the clergy were too ignorant to understand the Latin words they butchered in their offices and liturgies, if the ancient monasteries and collegiate churches lay deserted out of indifference, he was answerable before God, as Josiah had been. Alfred’s ultimate responsibility was the pastoral care of his people.

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of Ealdorman of the Gaini (who is also known as Aethelred Mucil), who was from the Gainsborough region of Lincolnshire. She appears to have been the maternal granddaughter of a King of Mercia. They had five or six children together, including Edward the Elder, who succeeded his father as king, Ãthelfld, who would become Queen of Mercia in her own right, and Ãlfthryth who married Baldwin II the Count of Flanders. His mother was Osburga daughter of Oslac of the Isle of Wight, Chief Butler of England. Asser, in his Vita asserts that this shows his lineage from the Jutes of the Isle of Wight. This is unlikely as Bede tells us that they were all slaughtered by the Saxons under Cwalla. In 2008 the skeleton of Queen Eadgyth, granddaughter of Alfred the Great was found in Magdeburg Cathedral in Germany. It was confirmed in 2010 that these remains belong to her — one of the earliest members of the English royal family.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_the_Great

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01309d.htm

/-1.407,51.5697,12/300x200@2x.png?access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoiamJlcmdlbiIsImEiOiJjanRxb3d1NWgwaHBuM3lvMzJ3emtyNWY4In0.xCCZGVjZrBAKn5C_O6q8CA)

/-1.3101,51.0598,12/300x200@2x.png?access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoiamJlcmdlbiIsImEiOiJjanRxb3d1NWgwaHBuM3lvMzJ3emtyNWY4In0.xCCZGVjZrBAKn5C_O6q8CA)